From: The San Jose Mercury

Date: Tuesday, August 13, 1985

THE COST OF QUESTIONED LOYALTIES

Japanese Americans Recall the Pain of 2 Countries’ Hate

By Teresa Watanabe

On the day the Japanese bombs demolished Pearl Harbor, Pete Nakahara got a taste of what was to come for Americans like him whose parents had been born in Japan.

Sitting in a Berkeley café with two friends, Nakahara – then a college student, now a San Jose lawyer – was listening with outrage and shock to news reports of the attack when the three men walked by.

Growled one: “If I had a gun, there’d be three dead Japs.”

For the next several years, Nakahara would share the special pain of that group of Americans squeezed by a war between their country and that of their ancestors – Japanese Americans, or Nikkei. Facing hatred and recriminations on both sides of the Pacific, they were “Japs” in America and “imin na kodomo” – immigrant children – in Japan.

Like his fellow Nikkei, Nakahara eventually proved his loyalty to America. But not before he had lost his father to insanity, endured his mother’s internment in an Arkansas camp and written to President Franklin D. Roosevelt protesting military racism.

* * * * * * * * * *

He was born May 21, 1921 [actually May 19, 1921] , in the busy shipping and fishing village of San Pedro near Los Angeles. Except for Japanese language school on Saturdays, Pete grew up as a typical California boy.

Or he thought so until the day he tried to do his American duty and enlist after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Although he was a good student at the University of California at Berkeley, and the winner of a statewide extemporaneous speech contest, Nakahara was rejected by the Army, Navy and Marine Corps. They told him they couldn’t accept Japanese American volunteers but that he might be drafted if his parents would sign a waiver for their son, who was one year shy of his 21st birthday.

His parents did so, and Nakahara was drafted at the end of December 1941. When he reported to Fort McArthur in San Pedro, he was put to work filling sandbags with a group of workers wearing large P’s on their shirts. Later he learned they were Army prisoners.

At Fort Warren in Wyoming, he was told he could not go to Iceland with the rest of the regiment because of his ancestry, and he was assigned instead to clean latrines.

Then he got an office job – but lost it after the first day when someone found out he was not Chinese. He was reassigned to unloading boxcars with a handful of other men, all of whom were black.

Protested racism

Finally he wrote to President Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Chief of Staff George C. Marshall.

“I said if they didn’t trust us, they should put us in a separate combat office and send us to Europe,” recalled the slim, tanned attorney, his voice devoid of bitterness.

“We wanted to prove to the American public that we were loyal Americans and deserving of equal treatment.”

Eventually, he said, they all wrote back and assured him that the Army was truly democratic and that they abhorred discrimination. By that time, his mother, older brother and twin sister were locked up in an internment camp in Jerome, Ark., under government order, and his father had died mysteriously.

* * * * * * * * * *

Seiichi Nakahara had entered the immigration-detention center on Terminal Island near San Pedro mentally alert and physically healthy, except for occasional asthma [actually Seiichi Nakahara suffered from stomach ulcers and diabetes, as well as severe asthma]. On December 7, 1941, immediately after Pearl Harbor, the entrepreneur, then 56, was arrested by the FBI as an enemy alien.

Attracted suspicions of FBI

In 1905, Nakahara had fled poverty in Morioka, a village in northern Japan, and built a prosperous wholesale fish company in San Pedro. His frequent contacts with Japanese shipping firms in the months preceding the attack on Pearl Harbor had aroused the FBI’s suspicions.

He sold fresh fish and other food to three Japanese fishing lines, though he also sold to the U.S. Navy. He entertained Japanese officers from the nearby merchant ships, one of whom the FBI suspected of being involved in espionage.

Like other Japanese community residents, he had donated money to a Japanese naval fund that was used to finance training missions to the United States. Nakahara also was a radio buff, and he had built two conspicuous aerials in his front hard to catch short-wave radio reports from Japan.

But, his son says today, Seiichi Nakahara was no enemy spy – just a smart businessman who kept up his overseas business contacts and still felt a natural affinity for his homeland.

What happened to his father while in FBI custody remains a mystery, Pete Nakahara said. He has heard reports that his father repeatedly was awakened at 1 a.m. and interrogated for hours, harassed as a “dirty Jap” by other prisoners and given no medicine for his asthma [or his diabetes – a deprivation that can cause delirium].

All Pete Nakahara knows for sure is that his father lost his mind and no longer recognized his son when he came to visit. “He refused to talk to me and said I was someone sent there by the FBI looking like his son to question him,” Nakahara said.

On Jan. 20, seven weeks after arresting him, the FBI suddenly declared that the elder Nakahara was not dangerous and released him. He died the next day. The family still does not know what caused his death [but suspect lack of medication for his diabetes], and the FBI told his mother not to mention the incident, Nakahara said.

No longer bitter

He said he doesn’t feel bitter about his own wartime experiences, but “I feel a sense of unfairness toward the treatment my father received.”

For his part, Pete Nakahara’s fluency in Japanese eventually enabled him to escape what he and the other Nikkei called their “s— detail.” He went to the Philippines to translate captured enemy documents and to broadcast surrender appeals to Japanese troops, and he interrogated Japanese prisoners of war in New Guinea. Later he served as a court interpreter for the War Crimes Trials in Tokyo and Yokohama.

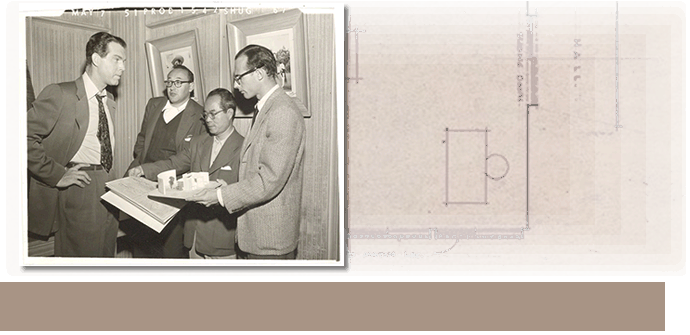

He married Aiko Umino, a civil service worker from Seattle, and completed law school at Stanford University. He went into private practice with a law firm, since disbanded, with Wayne Kanemoto in San Jose’s Japantown.

Kanemoto, a San Jose native and retired Santa Clara County Municipal Court judge, took his oath as a lawyer – pledging to support and defend the U.S. Constitution – while imprisoned in an Arizona desert camp.

After Pearl Harbor, when rumors of a mass internment began to percolate, Kanemoto was a law student at the University of Santa Clara. He wryly recalls his constitutional law professor assuring him at the time that “they can’t do this.”

But they did, sending him and his family first to a temporary center at the Santa Anita racetrack in Southern California, then to a permanent camp in Gila River, Ariz.

“Of course you feel you’re being treated unfairly,” said Kanemoto, who went on to Burma with the Signal Intelligence Outfit of the U.S. Air Force, translating Japanese communications and locating Japanese radio stations. “But it was wartime. In wartime, people do unreasonable things, including killing people.”

Still looking fit, with a mane of white-streaked hair, the 67-year-old Kanemoto makes jokes about his experiences. He likes to say that he is the only lawyer in California sworn in under the shadow of a saguaro cactus.

“I know it was wrong,” he said. “I tell people it was wrong. But I accept that everything is not always fair and do my best to correct it.”

Pete Nakahara, who now runs his own law firm, echoes those sentiments. The wartime experience has left him with more compassion, he said, and a stronger commitment to speak out against racial intolerance.

He is disturbed, for instance, by what he sees as a resurgence of racism against Asian Americans, including those of Japanese descent. He attributes that resurgence to trade tensions with Japan and to a backlash against the influx of immigrants from Southeast Asia.

Still, both Nakaharas and Kanemoto prefer to remain upbeat.

“Maybe I’m optimistic,” said Pete Nakahara, “but hopefully the American people can accept us as we are and not by stereotyping an image of what they think we are.”